Saturday, July 27, 2013

Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel - Timeless Flight

Timeless Flight (1976) ***

Reviews are subjective by nature, and while I honestly enjoy this album a bit more (considerably more on a good day) than the three stars indicated above, that's simply because I like Steve Harley. No, I don't mean that I know him personally - he could be an asshole in real life, for all I know or care. He's got one of those rare voices that simply oozes warmth and charisma - a bit like Roger McGuinn does (did?), with a similarly friendly, slightly straining tenor. The Cockney Rebels are present in name and perfunctory backup musicianship only: this is the album where Harley apparently decided to make his gambit for serious singer-songwriter. What that amounts to in practice is that we get an entire album's worth of mid-tempo, folky pop/rock songs stripped of any extraneous instrumentation that distracts from the words and the vocal delivery of those words - Harley's a man with a message, kids. Exactly what that message is remains unclear, shrouded by metaphoric obscurity even at its most topical ("Red is a Mean, Mean Colour," character assassinates Bolshevik U.K. politicians with Cold War paranoia, but you'd never guess that unless you already knew to look for it - then it all falls into place). Oh, "Understanding," is straightforward, alright - in a rather gruesome way. Harley had written love songs before, but never so bitelessly banal. "Don't Go, Don't Cry," is the second album lowlight - mellow funk was never Harley's forte; it rocks so mildly it inspires little more than toe-tapping, never mind booty-shaking. The rest of the album's six cuts are alright - just alright. nothing more; perhaps with the exception of the twilight loveliness of "All Men Are Hungry," the surefire cut-out for compilations. Harley almost seems intent on sheer hooklessness, avoiding any of his trademark oddball hooks that made him interesting in the first place - perhaps he thought those too gimmicky and glam too juvenile, but now he's grownup and making mature music for serious consideration. And if there's usually a recipe for a formerly exciting artist slipping into menopausal boredom, that's it. The album initially comes off as drab and monochromatic as its cover: classic Cockney Rebel swirled in kaleidoscope; solo Steve Harley steeps briskly in Earl Grey. However, adjust yourself to the sad reality of a deeply ordinary, musically unadventurous singer-songwriter album and you've got quite a good one - that is, if you're predisposed to like Mr. Harley and his sense of songcraft already. The album is too laidback by half - more Gordon Lightfoot than Bob Dylan, but hey I like Lightfoot, too, mellow easy-going melodics and all. "Nothing is Sacred," essays the best of that Lightfoot/Dylan style, over five breathless (literally) minutes of verbiage with no room for any other than a torrent of words. It's off-putting at first, but give it some time and it becomes cozy and comfortable. Same as the rest of the album.

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Mott the Hoople - Mott

Mott (1973) *****

Success under their rhinestone-studded belts, Mott must have known that the followup was crucial: either they delivered the goods or proved that they were little more than washed-up never-had-beens that David Bowie was gracious enough to toss a bone. And though it didn't produce a smash as huge as "....Dudes", it did amount to their biggest-selling album in the States, deservedly so: the band finally fulfill all the misspent promise they'd been building up to. And it only took five years and five albums to do it. Mott's only consistently powerful album isn't merely a substantial step forward in terms of songwriting and performance - it's one of the greatest rock albums in rock history, and easily the crowning masterpiece of the genre & era (Glim-Glam, yeah). The explosive boogie piano chords that open, "All the Way From Memphis," are practically the definition of rock'n'roll, and if you don't cop to that, I doubt that you ever understood Jerry Lee Lewis or purchased a second-hand guitar in a pawnshop. It's simply one of the greatest valentines to rock'n'roll ever penned, up there with Chuck Berry in his prime and Paul Westerberg bopping out his ode to "Alex Chilton". The rest of the album matches that standard - as the cliche goes, it's practically a greatest hits of all new material. The album's conceptual thread of the troubles and travails of a touring rock band may seem self-pitying and banal to modern ears, but at the time not that many had worn such meta-rock cliches into the ground, and few (any?) have done it better since. Ian Hunter's observations contain the telling detail of an ex-journalist and author of Diary of a Rock'n'Roll Star, and the fact that his band did indeed toil for years in groveling obscurity give his grumblings gravitas.

P.S. Of the bonus tracks, the B-side, "Rose," is a fine piano ballad - it didn't graduate to the album for obvious reasons (it wasn't quite good enough). But that says more about the strength of the 9 songs that did make it to Mott than any real weakness of "Rose". And R.E.M. namechecked it in "Man on the Moon," many moons later: "Mott the Hoople and the game of life / Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah."

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

Titus Andronicus - The Monitor

After ten thousand years, it’s still us against them

....and they're winning

The Monitor (2010) ****1/2

I've long taken the position that ambition does not necessarily equal achievement, but exceptions exist to be made: Patrick Stickles and the crew (over two dozen musicians listed in the credits, of which only the rhythm section is carried over from the debut) by no means achieve their outsized ambitions, yet that is only because their grasp is so absurdly huge. A 10 song, hour long concept album that employs the American Civil War as a metaphor for modern angst and frustrations, it's an intense, deeply exhausting listen, and as such difficult to soak in on first (or fifth) listen. With the exception of the twin fragments "Titus Andronicus Forever," and "...And Ever," which conceptually help tie together the first and second half of the album (they're the same song, more or less - the first take straight bruising punk, the second attempt looser barroom anarchy complete with honky-tonk piano; each last about a couple of minutes), the song lengths break down thusly: four 7 to 8 1/2 minute epics, three relatively short'n'snappy 5 minute mini-epics, and one 14 minute epic epic. Length only accounts for part of the exhaustion; couple that with the band's cacophonous overdrive and Stickles' impassioned (to the point of hectoring) vocals and lyrics that scream intense self-importance concerning his own self-loathing angst and the breakdown of contemporary American society (not necessarily in that order of importance) - well, this is one great album that you'll be glad to switch off and slump in your chair after it's finished firing its final volleys, as you wipe your grit-strained brow from the sonic and emotional assault. (In all fairness, Stickle's poor grasp of memorable melodicism has a lot to blame for that feeling, as well.) The weighty bits of quoted monologues linking the tracks together (Walt Whitman, Abraham Lincoln - who knows what other American icons) only show that Stickles is eager to show off that he's the son of a U.S. History high school teacher (well, so am I, so I can relate to his pretentiousness).

And it is a great album, not merely because it so desperately strains to be a Great Album (though that helps immensely). A formerly good but unexceptional indie rock band has emerged from the cocoon as a great band - much better production and performances all around, and the musical scope has transcended generic indie-punk to encompass lengthy guitar heroics, barroom boogie, piano balladry, he/she duets, drunken C&W (as filtered through the early Pogues), and bagpipe solos (yes - the last hard rock band to pull that stunt was AC/DC). It's not nearly as varied as that laundry list might lead you to except, but this sprawling double album (at over an hour, it's best to think of it that way) rarely falls into the monotony trap, in large part due to a trick pulled on several tracks: start off slow and Tom Waits-ish at the piano or strummy guitar, carry on in that gin-soaked vein for a dozen or so verses, as the music either slowly builds up to or jarringly lurches into the poundingly anthemic hard rock section. And if some of the sections are weak (the slow ones do underline Strickles' stunted melodic sense) - it's a sprawling double LP, that comes with the territory.

Each individual track may deserve an analysis equal to its bloated length, but in the interest of non-bloviation I'll limit myself to selected highlights (with my trusty yellow highlighter). "A More Perfect Union," militaristically calls the album to arms (shades of the Skids!) with a rouse-the-troops guitar solo that's as viscerally thrilling as the opening riff of "Bastards of Young" (the Replacements, youngsters). "No Future Part III: No Escape," starts off as an almost parody of stereotypically wimpy indie rock, until the drummer kicks it into second gear. Likewise, Strickles initially softly sings, "You will always be a loser," in the whimpering voice of a deservedly pathetic whiner, but by the end of the song has turned that same refrain into a defiant, inclusive, almost celebratory anthem. "Theme From 'Cheers'," is close to what you'd expect - a lament/celebration of the committed, lifelong drinking man's lot, sung with resigned bitterness and drunken gusto. And damn does it make me thirsty. Which is the highest compliment you can pay to a drinking song. We await until the end for the album's tour de force, the 14 minute, "The Battle of Hampton Roads," which only in the most superficial sense deals with the first battle of ironclads in naval history. By the end of the first verse Stickles has dispatched the Monitor and the Merrimack, and is ready to address more contemporary social grievances, both solipsistic and of wider societal import - "Is there a girl at this college who hasn't been raped? / Is there a boy in this town that's not exploding with hate?" - ranting full on for 7 1/2 minutes until he collapses melodically into the "please don't ever leave," coda, after which at approximately 9:15 in we're treated to the inevitable bagpipe solo, and the bagpipes & Celtic-spiked electric guitar carry us on out.

And so we conclude the first genuine rock masterpiece of the second decade of the 21st century (not that I'm all that hip with what kids dig today). That Titus Andronicus currently boast one of the most rabid fan followings in the country is understandable, even before you consider their live rep (catch'em while they're still young and before they've fossilized into 'legendary'). I wouldn't agree with some of the more rabid youngsters who claim that this is their favorite album of all-time (trawl RYM), given that I've heard 300 greater albums than this - but I've got some extensive knowledge of rock history. Kids for whom all of this is fresh - I'm not going to disagree with them. Which is an admission I would never begrudge any other hard rock band I've heard in the past decade - not the White Stripes, not the Black Keys, not even QOTSA. Titus are playing rock'n'roll with heart-on-sleeve emotion, passionate sincerity, and not a trace of irony - which you can't say about any of those other bands, and is an exceedingly rare commodity among Millenials. They aren't playing with a knowing wink in their eye, and they ain't twee & precious, neither. And that makes all the difference.

............................................................................................................

The first single was a 3 1/2 minute edit of a 7 minute song:

Flamin' Groovies - Supersnazz

1) The songwriting's thin - out of the 10 originals and 3 covers, not a single knockout. Nearly all of them score respectable base runs, but none hit'em out of the park or score home runs.

2) The major-label production sands the edges too soft - not a lot of grit in this boogie, which matters when you're rollickin' bar band.

3) The band has an overboard of influences and the eclecticism seems to overwhelm the band: as an Encyclopedia of Roots Rock, the variety keeps the album from ever sticking in a dulls-rut, but where do the Groovies seem to want to take those influences? The resultant sprawl can either be taken as assured exploration of American roots'n'roll or confusion as to what sort of band the band intends to be. Lessee -

Ragtime

'50s rock'n'roll (lots of that - mostly that, as you might expect)

Folk balladry

Hippie pop

Country & Western (more Western than Country - the Groovies did hail from Frisco)

Showtime vaudeville

Repetitive hippie pop chant ("Around the Corner," which works as a goodbye kiss and little else)

....anything I forgot? Probably, but track-by-track reviews are kind of a chore. This pleasant and enjoyable album doesn't live up to the promise of the cartoon cover - it's less a barrel of firecrackers than a head-noddin' toe-tapper. And while as I noted, none of the individual songs will bowl you over, the album works a good time magic definitely greater than the sum of its parts. The Groovies' debut aims for little more or less than a boogie hoedown, and sustains that lighthearted groove throughout without any real bummers disrupting the consistent flow. Its failure to attract much notice at the time (the Groovies were dropped by Epic after this epic fail) is due not only to no true knockout singles material ("Laurie Did It," comes closest), but the nature of the scene and its time. Only mild traces of Haight-Ashbury psychedelia rubbed their patchouli over the Groovies' grooves, aside from the groovy hipster name. The Groovies come across as more mellow and laid-back (man) than they would shortly become in their classic incarnation, which does fit in snugly with the hippie zeitgeist: it amounts essentially to late '60s roots-rock revivalism, with updated post-Hendrix guitar tones and slightly updated spaced-age sensibilities. The band would groove much groovier (groan), but this ain't a half-bad start.

Monday, July 22, 2013

Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel - The Best Years of Our Lives

The Best Years of Our Lives (1975) ****

Goodbye, Cockneys; hello, Steve. For whatever reasons of ego or dissension, the original Cockney Rebel broke up prior to this release, with only drummer Stuart Elliott to follow the leader. The music subsequently takes a drastic nosedive in terms of musical identity - precious little of the quirk and charm of the first pair of Cockney Rebel albums; instead it's mostly straightforward mid-'70s pop-rock soaked in by-then-conventional glam negligee. Around a decade or so ago, I made this my first toedip into Harleyland, and while I enjoyed quite a few of the songs, I couldn't quite figure out what the fuss was: he seemed like an entertaining, but highly derivative johnny-come-lately of Bryan Ferry and David Bowie. Now that I've heard him within the context of the first two Rebel albums, I can discern his unique talents; but it is only through that prism that one can distinguish every subsequent album as anything more than well-crafted, sometimes excellent but non-earthshaking mainstream '70s rock. Steve Harley the talented singer-songwriter remains intact, but Steve Harley the musical visionary has departed the building.

Get over that and what you are left with are 'merely' some great tunes with enticingly delivered vocals and cryptically intriguing lyrics. In fact, with Harley playing it relatively straighter (lyrically and musically), the songs are more immediately catchy and emotionally rewarding than anything off of the first pair of records. The title track may be a put-on, full of Dylan-esque straining towards grand import and emotional resonance, despite amounting to little more than a string of non-sequiturs - "Lost now for the words to tell you the truth / Please banter with me the banter of youth" - but damn if it isn't improbably moving in spite of itself. Harley may be putting on the mask of the sensitive troubadour for sport, but he sings richly (ah, that vocal may be the performance of his career) with such actor's conviction that he completely and convincingly inhabits the form. "Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)" is the track that towers above all the rest, however - center-pieced dab in the middle, and Harley's only #1 hit. Deservedly so: it's simply one of the greatest pop singles of all time, full stop. Harley's crisp crooning over the lush but sprightly bed of acoustic guitars and cooing background oo-la-la vocals, as he alternately disdains and implores his potential conquest - you'll think it's tragic, but it's magic, it's the best single of 1975. And that Spanish guitar break is pure icing. "Mr. Raffles," was the more than worthy follow-up, not quite as magical (how could it be?) but a hit in its own right, and one of Harley's most lyrically intriguing: late-period Dylan gone Elton John is the best I could describe it, with the clever sound effect of cracking maracas immediately after the "you shot that Spanish dancer," line always giving me a chuckle. The paranoid, "Back to the Farm," is the key 'deep album track', a moody set-piece that is very, very Roxy-esque, underscored with Eno-esque synth squeals if you missed the point. If I had to pick a weak track, it would either be the mild (very mild) quasi-funk of "49th Parallel," or the atmospheric but hookless, "It Wasn't Me," all drifting six minutes of it. But neither are bad, just forgettable - this may not be Harley's most adventurous album, but it is perhaps his most consistently tuneful one.

Bonus tracks: "Another Journey," is a melodic gem that should've graduated from B-side to album track (replacing either one of the two aforementioned weaker tunes). The live version of "Sebastian," stretches on for nearly 11 minutes, which isn't undeserved, and certainly gives Harley's vox a good workout - if you want to hear the man at his most throat-shreddingly impassioned, here you go. Maybe "somebody called me Sebastian," actually did mean something deeply personal to Steve, after all.

Stupid coat.

Sunday, July 21, 2013

The Idle Race - The Birthday Party

He gets out of his face with the Idle Race /

He gets out of the room with this tune

- the Fall, 1979

The Birthday Party (1968) ***1/2

Initially I naturally thought of the Idle Race as imitating the Move imitating the Beatles, but with a lighter, softer pop touch in contrast to the Move's somewhat doomy Who-derived rocking. On second listen, I noticed that the very-velly English whimsy and music hall influences spiced liberally with the softer edges of psychedelia put me more in mind of the Idle Race imitating Syd Barrett imitating the Kinks. In final conclusion, however, this sounds like a preview of Wings. It's exactly the sort of post-psychedelic, post-Beatles, post-pot damaged nonsense that Paul McCartney would pump out circa "Admiral Halsey". In other words, it sounds like a dead ringer for Dukes of Stratosphear era XTC aiming for The Bee Gees' 1st. If this fundamentally childish album weren't so bloody fun it would be impossible to take seriously.

First a little biography. The guy in the Afro is Jeff Lynne, later of the Move and even later of ELO, but of course most infamous as the fifth Traveling Wilbury. The Idle Race were formed from the ashes of a beat-era group known around town as the Nightriders, which featured an up and coming Roy Wood before he was poached as the chief genius behind the Move. A teenage Lynne was drafted in as a replacement, and their debut single was....a cover of the Move's "Here We Go 'Round the Lemon Tree." Naturally, given all those incestuous ties within the Birmingham scene, the Idle Race never quite shook off (then or now) a little kid brother to the Move rep. And in all fairness, such a reputation wasn't unwarranted - the music here is very Move-like. I rate the Idle Race just a notch or two below the Move simply for the fact that the Move's harder rocking tunes sound bigger and more fully developed; the chintzy production values write the Idle Race's music on a more miniature scale. However, even at this point, Lynne's songwriting skills were quickly catching up with his slightly older mentor's.

One other distinction from the Move is that the operative word here is 'childish': the Idle Race were clearly aiming for what may be described as 'bubblegum psychedelia', more "Yellow Submarine" than "Tomorrow Never Knows". Tastes are tastes, and I can completely sympathize with those who find the likes the absolutely idiotic "Sitting in a Tree," charmingly sing-a-long rather than Forrest Gumpish. Likewise, a few other simplistic novelty numbers such as, "(Don't Put Your Boys in the Army) Mrs. Ward," and "I Like My Toys," (yes, a real title, and indeed as childish as you'd expect) spoil my appetite. The proximity to such stuff slightly mars more substantial fare, such as the gorgeous "Morning Sunshine," and "The Lady Who Said She Could Fly," which demonstrate that even as a tender prodigy, Lynne's hypermelodic abilities had arrived fully formed. The title track was a wise choice for a single (even if it undeservedly flopped, like every other Idle Race single): beginning with a 23-second mock-orchestral (foreshadowings of ELO!) snippet of the most widely-known song in the English language, it leads to a mock-melodramatic, faux-melancholy ballad concerning a girl who commits suicide because no one remembered her birthday. With exception of guitarist Dave Pritchard's "Pie in the Sky" (fine little tune) and that snippet of "Happy Birthday," all of the 13 tunes are Lynne originals. A not insignificant feat in an era when most bands still relied on covers to pay the bills. Maybe this kid might amount to something someday. In short, while this music is by no means essential to any but diehard British Invasion fanatics, it is likeable and fun, not to mention a nifty appetizer for greater achievements to come.

P.S. In keeping with U.K. practice of the day, gems such as "Imposters of Life's Magazine," which were released earlier as singles, did not appear on the debut album. Wanted to avoid overlap, you see. And since there is no CD reissue with bonus tracks currently available, you'll have to look those singles up yourself. Such music as this has grown somewhat overrated over the passing years due to its inaccessibility, but we are fortunate enough to live in the age of Youtube. Enjoy and indulge for yourself!

Saturday, July 20, 2013

Mott the Hoople - All the Young Dudes

All the Young Dudes (1972) ***1.2

Apologies to Cracked.com for borrowing a cartoon I saw the other day:

This sums up the malady Mott's fifth album suffers from: there are quite a few slabs of more than respectable examples of glitzy cock rock (and for once I do not mean that as insult; it's an objective observation) on this disc. But nothing comes remotely close to matching the emotional and melodic power of the title track, a more than generous donation from David Bowie (he should be awarded a lifetime achievement for philanthropy), a song of such anthemic ubiquity it virtually defines the early '70s, and had the double-edged blade of not only breaking Mott in America but having Mott written off as otherwise forgettable one-hit wonders and no-talent puppets of Mr. Ziggy Stardust. Credit good karma to Bowie not merely for penning Mott's greatest hit - he also effectively rescued the band from breaking up, as they were about to do upon returning to Blightey after a disastrous European tour. According to Ian Hunter, the band also took lessons in professionalism from Bowie - for the first time they actually took care in rehearsing and arranging their songs, instead of just "spewing it out like a gig." Thus, their debut for CBS Records crunches sleekly and swaggers tightly in a quantum advance of musicianship over their Island Records albums.

So why don't I rank this a half star ahead of Brain Capers when it's a clear entire star (and maybe a half) step up in musical quality? Simple: it's lacking some crucial elements that endear fans of Mott, despite (because of?) how crappy they could be. To start - emotional heft, for lack of a better descriptor. Oh, and the untamed, desperately unhinged bar-room brawl anarchy that characterized their first four albums. Sure, Mott were a complete mess that failed more often than they succeeded, but they were what modern kids today would call a hot mess. Bowie's tutelage and production reign the band in tightly, but the effect is a little arid and calculated when compared to, say, "Thunderbuck Ram." And with the exception of the title track and the closing piano ballad, "Sea Diver," Hunter the thoughtful and introspective poet of noble loserdom is nowhere to be found. The band simply offer up one tight, hot, crunchy, sleazy glam rock anthem after the other - after a while some of these might seem a little interchangeable, but they're helluva fun while cranked up. Just don't take stuff like the one about a girlfriend's oral skills followed up by the one with jerkin' in its title to heart - geez, maybe Bowie's influence rubbed off (huh huh Beavis) a little too much. The band were mistaken for homosexuals when they toured the States, after all, due to "Dudes," and a juvenile delinquent anthem entitled "One of the Boys". Anyway -

High point: a cover of the VU's "Sweet Jane" that is definitive, despite Hunter being on record as believing that the song was shit, Lou Reed was shit, and the VU were shit, too.

Middling point: Mick Ralphs' "Ready for Love," superior to his later reworking for Bad Company, but unwisely stretched out to nearly seven minutes due to the pointless "After Lights," jam.

Low point: Verden Allen still cannot write songs but he insists on putting them on albums anyway. Worse, he tries to sing "Soft Ground" - if you thought Ian Hunter was a weak singer, you ain't heard nothing yet! Still, the downplaying of his keyboards on this album (in favor of pumped up guitar riffage) is a blow to Mott's distinctive musical identity. After this album, he'd be gone, and thus unable to partake in producing Mott's masterpiece for the history books. This one ain't it, but it does take a few valuable steps in the right direction.

Siouxsie and the Banshees - Juju

Juju (1981) ****

The band tried these tunes out in a live setting first as test runs, and that makes the crucial difference: while the studio hide-bound Kaleidoscope coasted a little too easily on sonic gimmickry and atmosphere, Juju offers much more immediacy and energetic rock power. It actually takes a step back from the previous album's eclectic adventurousness, recalling the black & white monochrome of the early Banshees - but like the cover, there are enough splashes of color to keep things from the curse of too same-samey. Sonically, it's essentially a jangle-pop album charged with electric punk intensity; moodwise, it's - well, what do you expect? Roses and peanut butter? It's dark and goth, duh. On the heels of the first Banshees Mk. II album, by their sophomore release they have confidently gelled into a tight, hard rocking unit, with Budgie's drums brewing up the right kind of tribal voodoo for Siouxsie to lay her improved (even tuneful....at times) vocals atop. However, it's John McGeoch who takes center stage as the star hero: his tinny, scraping, abrasive guitar finds a tone that manages to jangle and slice at the same time, and provides most of the meat & muscle & color for these nine tunes (not many keyboards this time - it's all straight guitar pop). The most underrated post-punk guitarist? Source of trauma for Howard Devoto for letting him go? The missing link between Andy Gill of Go4 and Johnny Marr (cited influence)?

Initially I slated Kaleidoscope as slightly superior due to its much greater variety, but the Banshee's gloomiest platter is also their most consistent - not a whole lot of filler here, with the notable exception of the closer, "Voodoo Dolly," which imitates a brooding Doors set-piece for seven boring and melodramatic minutes. The album begins exceptionally strongly with four commanding cuts in a row. "Spellbound," jangles like Grace Slick shaking tambourines around the campfire at dusk, which only goes to show that at least a certain segment of punks were just hippies too young to experience the '60s firsthand. "Into the Light," and "Halloween," are pulsating mid-tempo and pulsating punky rockers, respectively, both showcasing the propulsive rhythm section and McGeoch's chiming post-glam guitar cutting and droning. The single "Arabian Knights," soars on snaky Orientalist melodicism as the clear A-side; its protest against women, "Veiled behind screens / Kept as your baby machine," probably wouldn't fly in these politically correct times, no matter how politically accurate the feminist criticism actually is. I'm sure Edward Said published a theoretical dissection and protest in the Arab Studies Quarterly. Of the remaining cuts, only the moodily grinding, "Night Shift," (a six minute epic that actually works, unlike "Voodoo Dolly"), matches the standard of the first half; but while "Sin In My Heart," may be so overly minimalistic that one suspects a throwaway, it jingles as the most energetic track (Banshees do the Ramones?), and "Head Cut," has the most....interesting lyrics. As for, "Monitor," - well, it's sort of there. But it does have a great guitar tone - like the rest of the album. If you're at all interested in the band, this is easily the best place to get acquainted.

Friday, July 19, 2013

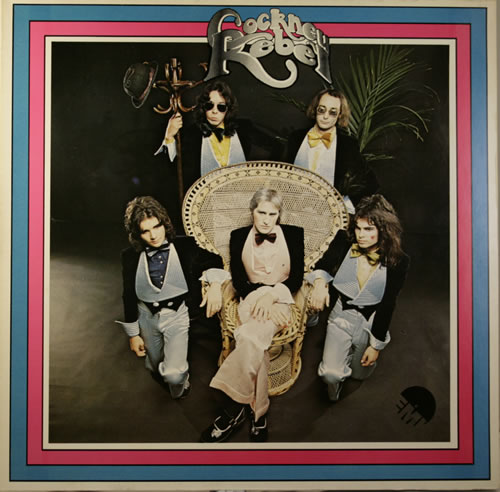

Cockney Rebel - The Psychomodo

The Psychomodo (1974) ****1/2

A dash more rock and a new ingredient of Doors-y swirling carnival keyboards: the rock'n'roll circus is in town. It's ever so slightly superior to the debut (and I can easily see others switching my ratings between the two) due to the songs being somewhat more straightforward and more immediately hooky - a year's span had apparently given Harley time to sharpen the soft focus of The Human Menagerie into more consistent songwriting. It comes down to a battle between the debut and the followup's pair of twin epics. The ridiculously over-phased, repetitive "Ritz," almost sounds like a parody of glam psychedelia, the sort of goof that Ween might have written if they'd ever tackled a mock of that genre - but wait, when's the last time you ever heard any glam psychedelia? Todd Rundgren? Aladdin Sane? It may be meaningless, but it's a gas - man. Perhaps it wasn't the brightest of ideas to sandwich that one and "Cavaliers," back to back - these two plodding Big Statements take up nearly sixteen minutes between the two of them, nearly sucking the life out of the record. Not that either are bad, but a pair of draggy, druggy epics in a row? I do see that on the original vinyl that they weren't back to back, actually - one closes side one and the other opens side two. Nevermind - "Cavaliers," is even better (though, again, I do see how another person might switch the preference for "Ritz"), with jumbo-sale '67 Dylanisms rousing up to the gospel, "Testify, testify, testify" chorus.

But as if a photo negative of the debut, it's not the overblown epics that dominate the record, but rather the shorter, snappier tunes. The title track swings propulsively (contradictory as that may sound) on rinky keyboards lifted from the puppet show, as Harley sings agitatedly and affectedly (another contrast!) about Quasimodo, George Orwell, ex-Beatles, and suicidal streets. "Mr. Soft," the lead single, is mighty odd material for a hit A-side: a dark and stern yet baby-bouncy Kurt Weill-ish waltz-march that oomphs and chugs along with a sinisterly creepy circus clown's grin. It conveys the funhouse-mirror dark side of the carnival better than almost anything the Doors ever did. The bright'n'raffishly charming sleaze-pop of "Bed in the Corner," might have made a better choice as single, with its irresistible melodic lilt and identifiable failed-rake lyrics; but it's inextricably intertwined with the electric violin-fest of "Sling It!" that buzzes in the ears like a thousand mosquitoes in tune - the way the initial mid-tempo pop tune meshes into the high-energy dance stomper makes for one of the most startling track-to-track mash-ups ever. And then the album crashes down on its final and mightiest (?) tune, "Tumbling Down," which could be called yet a third epic or just another pretty pop tune: it begins as a standard, meandering Elton John-ish piano pop song, as Harley winds his way around typically enigmatic poeticisms concerning the Titanic, the Hemingway stacatto, and suchlike. It's all a pleasant enough stroll down the long and winding road, until it slowly builds up to the, "Oh dear, look what they've done to the blues, blues, blues?" closing chorus - and then it's sheer magnificence.

P.S. The reissue appends two bonus tracks, the single "Big Big Deal," which is rather unexceptional. It's bit baffling as to why this was chosen as an A-side when it sounds like a slightly inferior outtake from the accompanying album. The B-side "Such a Dream," is a novelty track that stretches two minutes' worth of one-trick pony shock tactics for over five minutes. Offbeat novelties that weren't quite worth the musical meat to graduate to LPs are the reason why B-sides were invented.

Thursday, July 18, 2013

Mott the Hoople - Brain Capers

And to those of you who always laugh

Let this be your epitaph

Let this be your epitaph

Brain Capers (1971)***1/2

Bashed out in a mere week as a final, frantic gasp before they were dropped by Island Records, Mott's fourth album ironically turned out to be the most consistent of their pre-glam albums. The live in the studio feel suits a band never renowned for its subtlety or polish, but earned their rep as a barnstorming stage act. After 'three strikes you're out' failures to translate that rep into any sort of crossover success, the bitterness and bile boil over on Mott's heaviest and most metallic album: "How long before you realize you stink?" Ian Hunter spits out on the funky choogle of "Death May Be Your Santa Claus," which does indeed live up to its title. With Verden Allen's murky,

droning organ dominating the sonic landscape, the band bashes it out with almost physically bruising force, as Hunter croaks in his patented, "I can't sing worth a damn and who gives a shit?" sub-Zimmerman strain. After that, catch your breath for a bit of light relief with a folky cover of Dion's "Your Own Backyard," - but no, you don't catch a break from the intensity just yet, as the anti-drug lyrics hit you like a subtle flying mallet. As you can tell from the title, the Ralphs-sung cover of the Youngblood's "Darkness, Darkness," isn't the light relief you've been seeking, either - howling metallized soul is more like it, though not nearly as effective as the previous two songs. "The Journey," stumbles through the desert for eight and a half minutes (have they learned nothing from "Half Moon Bay"?!), grinding the album to a dullsville halt. Now, "Sweet Angeline," - that's the light relief we've been waiting for: a roller-rink organ roller of a pop tune that could've drifted in from the debut album, laughable but charming dead-on Dylanisms and all. Unfortunately, at this point Verden Allen was flexing his muscle by shoving at least one token tune upon the band's records, despite the fact that he had close to zero talent as a lyricist or composer: the Spanish horn drenched "Second Love," proves that John Entwistle he ain't, and is the second major dud. Yet Mott save the best for second last: "The Moon Upstairs," blasts out of the heat furnace as a relentlessly propulsive proto-punk classic, the band droning like the VU's nightmares and roaring like the Stooges' British cousins. Hunter babbles some motorpsycho-Dylan tale of the police setting his body free but locking away his brain, as he wanders free as a bird with a broken wings, and takes time out in the bridge to insult the audience: "We ain't bleeding you, we're feeding you, but you're too fucking slow," he sneers with fed-up frustration. The final track, "The Wheel of the Quivering Meat Conception", is nothing more than a minute and a half audio pastiche that

contains the sounds of a party over music repeated from "The Journey". Filler, they tend to call it.

26th March 1972, Zurich: a date the band would memorialize in song a year or so later. Mott play a club converted from a former gas tank, take a good hard look at their career prospects, and agree: "If this is fame, forget it," (as Hunter put it). Cue David Bowie to the rescue....

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Aztec Camera - Knife

Knife (1984) ***

The dreaded rot of artistic maturity has already set in, even with Roddy Frame still a wee lad of twenty. Almost perversely seeming to distance himself from the debut's rushful songs of innocence, these songs of experience pull Frame in two differing, but overlapping directions: singer-songwriter troubadour under the tutelage of producer Mark Knopfler (not as Dire as you'd think, though) and the MOR yuppie soul that Roddy would soon sell out to. Call it a transitional album, then, as musically this falls halfway between the debut (it's still mostly acoustic guitar based) and the third album, Love (considerably more produced, with chintzy atmospheric keyboards abundantly over some of the tunes - ah, the '80s). The main problem isn't the soft-rock '80s production, however - it's that Frame seemed to have made the rookie mistake of equating 'mature' and 'thoughtful' with 'slower' and 'more self-important'. The dreary 9 minute title track is the biggest offender, trailing on seemingly forever on ponderous atmosphere and little else, but thankfully nothing else here is nearly as dreadful - though the equally furrow-browed "Back Door to Heaven," comes close (and yes, the sex pun is just way too obvious, even for Mark Prindle). The hit single, "All I Need is Everything," amounts to perilously anonymous '80s pop, with those keyboards washing over atmospherically - we're not in indie-rock land anymore, Toto. We're in '80s Toto land. And what's up with that cheesy and pointless Spanish guitar coda? Mind you, if this review is seeming too harsh - I haven't gotten to the good tracks yet! Perhaps the entire album would've been better released as raw acoustic demos, as the excellent "The Birth of the True," proves - that's where your true talent lies, Roddy, it's shining through loud and clear here. The three first tracks likewise would've fit in fine on the debut: the jumpily anthemic "Still on Fire" (should've been the first single); the loping melodicism and emotional resignation of "Just Like the USA"; and the gentle melancholy of "Head is Happy (Heart's Insane)". Pity it all has to go pear-shaped after such a promising start. But if you're lucky, you stumble upon an edition that contains Frame's brilliantly languid, acoustic take on Van Halen's "Jump" - genius! And easily the greatest version of that song - Frame reveals the melodic pop brilliance hiding at the center. It's easily enough to render an extra half star to the rating.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

The Fall - The Marshall Suite

The Marshall Suite (1999) ***

Important biographical note (pay attention!): some months prior to this release, Mark E. Smith was arrested during the Fall's American tour for beating up keyboardist/latest Mark E.-squeeze Julia Nagle. The rest of the band quit in disgust, including the only other remaining founding member, Steve Hanley (and his bass lines are sorely missed). Curiously enough, Nagle herself stuck around. So Smith hired a garage band from scratch and amazingly (or not so amazingly) enough they still sound exactly like the Fall. In fact, this sounds little different from almost every other '90s Fall album: a little rockabilly, a little garage rock, a lotuva electronica, some token piano balladry. A little something for everyone that only half-pleases everyone: like many other artists into their third recording decade, at this point there's not much hope of converting neophytes - but unlike most other artists into their third decade, Smith is still capable of delivering well-crafted product that satisfies the fans. This relatively short (by late-period Fall standards) LP of 39 1/2 minute length doesn't make the mistake of wearing out its welcome, and starts out very strongly, but seems to lose the plot somewhere halfway through. The Nuggets-style lead single, "Touch Sensitive," is a welcome return to garage-rocking primo Fall (but when did they ever completely abandon that style?!), and the cover of the rockabilly obscurity, "F-'Oldin' Money," is stratospherically better (OK, maybe not stratospherically superior, but it is stratospherically F'n good). The rock'n'roll portion of the programme out of the way, the rest of the album rocks more dancey - still plenty of abrasive hard rock guitar, but more clip-clop or trip-trop or whatever y'call'em beats meats manifestos. "The Crying Marshal," is easily the best of that lot, and one of the most crushing dance-rock pounders they've ever produced, with ultra-fat (I'd say phat but I'm not that hip or retarded) drums tom-tomming and guitars & keybs nagging like buzzing dragonflies. There's a cute little jangly pop tune ("Bound") that's a mite too repetitive (maybe I'm listening to the wrong band if that's going to be a complaint), a lethargically sung but rushingly played cover of the Saints' "This Perfect Day," and some more cute little gentle whistling'n'jangling pop ("Inevitable"). And just to remind you that they are the Fall, there's a couple of minutes of "experimental" crap ("Mad.Men-Eng.Dog"). An inconsistently written and performed consolidation of Fallmusic without any major steps forward, but a not inconsiderable improvement over the previous couple of Fallreleases.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

Public Image Limited - This Is What You Want... This Is What You Get

This Is What You Want... This Is What You Get (1984) *1/2

I'm almost tempted to award bonus points for blunt honesty. With Keith Levene departing prior to the sessions, of the original core creative trio only Johnny remains - from here on out PIL are essentially the John Lydon Experience. And though Rotten does play a few keyboards and synth bass on the album, he is still for all purposes a non-musician - he's admitted that working with the faceless studio musicians amounted to, "me giving orders and them receiving them. There was no feedback. If I had a crap idea, the crap idea would go on to vinyl almost directly!" In the realm of art, honesty is no saving grace, unless you count Lydon's continued ability to annoy excruciatingly - in that case, this album is a masterpiece! Most immediately audible annoyance: the horn section, which sounds all at once tinny, squawky, sour, and synthesized. And those damn horns are splattered annoyingly over almost every single track. It's the aural equivalent of recording your own farts and then punching them into the mix at random intervals. Some of these songs would've been passably OK if not for the horn punctuations. A hornless "This is Not a Love Song," proved that theorem a year earlier as a U.K. hit; you just had to re-record it without Levene and ruin it, didn't you? Likewise, the anti-child abuse, "Tie Me to the Length of That," sounds like it could've drifted in from the previous album if not for the horns, and in this context the spare, "The Pardon," which consists of little more than drums and chant, comes as a relief from the oppressive brass section. Not that it's still crap, but at least it doesn't have synthesized horns. And there's problem #2 - as Lydon possesses no innate musical skills, nor a strong collaborator to help with that side of things, the dance-poppy songs are seriously underwritten - mostly repetitive chants that hang loosely on clip-cloppy drums and Lydon't trademark granny-cat mewls. And irritatingly enough, just when you're ready to write the entire album off as a complete waste of tape, comes the final track, "Order of Death," a quasi-instrumental that's - well, I wouldn't quite call it a gloomy, spacey post-punk "masterpiece", but is an excellent track that by no means deserves the company of the rest of the album.

P.S. Most of the tracks that wound up on this album were originally recorded with Keith Levene, but after his departure, those tracks were re-recorded with Levene's guitar parts erased like a Stalinist photo purge. Levene released his own version of this album entitled Commercial Zone, which consists of those early demos. I have no interest whatsoever in listening to or reviewing that, but maybe the 3 or 4 PIL fanatics out there might care. But then again, if you are indeed a PIL fanatic, you are already aware of this information, and thus my input is useless. Much like this album.

Here, take the original 1983 single version of "This is Not a Love Song," before the horns ruined it.

Now compare and disgust:

I apologize for making you listen to that same song twice. Is this better?

Monday, July 8, 2013

Cockney Rebel - The Human Menagerie

The Human Menagerie (1973) ****

The reviewer is left stumped trying to describe this album. Not that the music itself is all that out-there; this is first and foremost a creamy pop album, gentle and strange and full of accessible melodicism (if non-obvious hooks; but a little work digs the hooks out eventually - and they're worth the digging). Making their entrance at the height of glam's heyday (just at the tail-end when the decline of glitter-rock as a commercial and artistic force was setting in) the Cockney Rebels bear some superficial similarities to early Bowie, Queen, and (especially) Roxy Music. But like Roxy, the glam tag only superficially suits them: the music is a mite too complex and art-rocksy (but definitely not prog), not to mention idiosyncratic, to fit comfortably within any genre boxes. Unless you count that vaguest of genre terms, Art Rock - yeah, that fits the bill. Or more precisely, Art Pop, since one of the album's gimmicks is No Electric Guitar! - instead, the primary stringed instruments are trusty acoustics and Jean-Paul Crocker's electric violin. The rhythm section don't so much rock as roll, adding a distinctly calypso feel to a number of tracks (dig those vibes). Add splashes of lounge-lizard keyboards and Steve Harley's distinctive tenor vocals, and you might begin to describe the basic formula - but your ears are better than my feeble words; this stuff is just too sui generis to peg. Harley's vocals are almost as idiosyncratic as the instrumental backing; perhaps a bit too Cockney for some, and he's definitely mincing some affectations in his enunciations, but much pleasanter on the ears than his closest cousin Bryan Ferry, and betraying a clear Ray Davies influence. And like the Kinks, Harley bears the distinctive stamp of (decidedly British) music hall, with an extra-strong dose of camp theatricality.

But unlike R. Davies, Harley's lyrics are anything but straightforward - on first scan (and second, and thirty-third) they seem like disassociated, randomly 'poetic' lines that make no literal sense but simply sound good. And half the time you'd be right. What does the gloomy epic (complete with 50 piece orchestra!) "Sebastian," mean, if anything at all? The way Harley portentously croons, "Someone called me Sebastian," with orchestral crescendos billowing behind the chorus, artificially inflate it to importance, but really - does even Harley himself understand what the song's about? "Your lips ruby blue, never speak a sound"? Harley's lyrics flow with the non-linear logic of dreams, and combined with the eccentricities of the music, give the album a bit of a surrealist feel. The album's other extended epic, the nearly 10 minute, "Death Trip," makes only slightly more (less?) sense, and contrary to title, isn't gloomy or gothy at all - just soft piano pop with sawing violin and orchestra surging in the background. The remaining eight songs are considerably shorter and poppier than those two epics, with the opener, the Spanish guitar driven "Hideway," being of particular excellence, and the weakest track, the fiddle-dance "Crazy Raver," being only slightly irritating and only slightly weak. Unless you count as weakest, "Chameleon," which at 49 seconds swings by too fleetingly to really register. "Mirror Freak," with its reference to a certain narcissistic elf, is indeed about Marc Bolan, for you rock trivialists. Appended to the reissue are two bonus tracks: the rhythmically intricate "Judy Teen," single, with the main hook residing in the stop-start of the rolling drums; and the B-side, "Rock and Roll Parade," which in actuality is more square-dancing fiddle-pop.

A very strong four stars, then - almost four and a half, but I like the next one even better.

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Siouxsie and the Banshees - Kaleidoscope

Kaleidoscope (1980) ***1/2

What a difference a major lineup change makes. With half of their band departed, leaving only bassist Steven Severin and Siouxsie herself, the Banshees carried on by drafting a drummer (and future Mr. Siouxsie Sioux) named Budgie, and a pair of guitarists, one of whom used to be in a band called the Sex Pistols. But it's ex-Magazine John McGeoch who's the real catch; in my review of Magazine's first post-McGeoch LP, I noted how drastic and unexpected a blow his departure was to that band. One post-punk band's loss tis another's gain, and unsurprisingly given that this is essentially an almost entirely new band, the Banshees do sound like a completely different band. That much is immediately apparent from the very start, as the guitars in "Happy House," chime gently rather than abrasively, ringing through a tune that's more melodic pop than grinding punk, and the attitude more becalmed goth resignation than punk indignation. While the first two albums could rightfully be accused of being shot in monochromatic black & white, the music here explodes in colorful splashes as advertised by the only slightly hyperbolic LP title. Such a drastic shift of direction was sorely needed after the disaster of the second album, and with the music opening up to a richer, more textured goth-pop rather than goth-punk style, the Banshees as we stereotype them have arrived.

It's not so much a transitional album as a full-blown explosion into a new style, yet the album does display a few niggling and naggling missteps into that new style. Namely, the band seem so intent on exploring new sonic directions, lavishing so much attention on mood and texture, that they take a bit less care with the songwriting. Tracks like the spare, bass-driven "Tenant," and the wordless rush of "Clockface," (the most energetic number, spaced-out big beat that's a bit reminiscent of the Police's "Regatta de Blanc") work most finely; "Lunar Camel," and "Desert Kisses," however, vamp on too dependently on atmospherics to cover up the thinness of the tunes. With the exception of "Happy House," and "Christine," none of the album tracks leap out as potential singles material (and yes, those two were the actual singles, unshockingly). The split-personality anthem from whence the album derives its name, "Christine," in particular is a classic slice of surging goth jangle. Elsewhere, Siouxsie pursues her obsessions with the fragile human body and the perversity of its beauty-standard presentations ("Skin", "Red Light," and "Paradise Palace," which offers the album's most arresting lines, "Hide your genetics under drastic cosmetics / But this chameleon magic is renowned to be tragic"). Rather hypocritical lines to pronounce from the rouged lips of a person who pancakes her natural features underneath layers upon layers of makeup, isn't that?

What a difference a major lineup change makes. With half of their band departed, leaving only bassist Steven Severin and Siouxsie herself, the Banshees carried on by drafting a drummer (and future Mr. Siouxsie Sioux) named Budgie, and a pair of guitarists, one of whom used to be in a band called the Sex Pistols. But it's ex-Magazine John McGeoch who's the real catch; in my review of Magazine's first post-McGeoch LP, I noted how drastic and unexpected a blow his departure was to that band. One post-punk band's loss tis another's gain, and unsurprisingly given that this is essentially an almost entirely new band, the Banshees do sound like a completely different band. That much is immediately apparent from the very start, as the guitars in "Happy House," chime gently rather than abrasively, ringing through a tune that's more melodic pop than grinding punk, and the attitude more becalmed goth resignation than punk indignation. While the first two albums could rightfully be accused of being shot in monochromatic black & white, the music here explodes in colorful splashes as advertised by the only slightly hyperbolic LP title. Such a drastic shift of direction was sorely needed after the disaster of the second album, and with the music opening up to a richer, more textured goth-pop rather than goth-punk style, the Banshees as we stereotype them have arrived.

It's not so much a transitional album as a full-blown explosion into a new style, yet the album does display a few niggling and naggling missteps into that new style. Namely, the band seem so intent on exploring new sonic directions, lavishing so much attention on mood and texture, that they take a bit less care with the songwriting. Tracks like the spare, bass-driven "Tenant," and the wordless rush of "Clockface," (the most energetic number, spaced-out big beat that's a bit reminiscent of the Police's "Regatta de Blanc") work most finely; "Lunar Camel," and "Desert Kisses," however, vamp on too dependently on atmospherics to cover up the thinness of the tunes. With the exception of "Happy House," and "Christine," none of the album tracks leap out as potential singles material (and yes, those two were the actual singles, unshockingly). The split-personality anthem from whence the album derives its name, "Christine," in particular is a classic slice of surging goth jangle. Elsewhere, Siouxsie pursues her obsessions with the fragile human body and the perversity of its beauty-standard presentations ("Skin", "Red Light," and "Paradise Palace," which offers the album's most arresting lines, "Hide your genetics under drastic cosmetics / But this chameleon magic is renowned to be tragic"). Rather hypocritical lines to pronounce from the rouged lips of a person who pancakes her natural features underneath layers upon layers of makeup, isn't that?

Titus Andronicus - The Airing of Grievances

Spot the influence adds up to a Rorschach test for the contemporary listener: while a respected elder like myself might hear another chip off the early Replacements (hey, the band does cover "Kids Don't Follow," in concert), kids whose fresher memories go all the way back to the early '00s will hear this as Conor Oberst fronting a heavily-fuzzed, keyboard-less Arcade Fire; while the generation in between us will hear traces of …And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead (what a ridiculous name to type) and Archers of Loaf (what an even more ridiculous name). In other words, it's perilously close to generic indie rock; played with an excess of enthusiasm and hi NRG, but on initial impression a bit too faceless to stand out of the pack. (Oh, and listeners even older than me? Let it be known that the band are from New Jersey, are inclined to lengthy, air-punching anthems, and are rumored to put on a helluva live show. In other words, some critics feel obliged to drop in a gratuitous Springsteen comparison.) And speaking of reference points: the band's name comes via Shakespeare and the album title via Seinfeld, which demonstrates that the band has one foot in artsy pretensions and the other in post-modern pop culture (but doesn't every band feature the latter these days?). And speaking of literary pretensions, one track does indeed feature frontman Patrick Strickles reciting a speech from that Shakespeare play. The final track includes a recitation from The Stranger. The track is helpfully entitled "Albert Camus". Another track bears the title "Upon Viewing Bruegel's 'Landscape with the Fall of Icarus'". Yes, the lad seems intent on demonstrating that his liberal arts education was not entirely wasted after he wound up fronting a sweaty, beer-soaked bar band for his post-collegiate career. (Strickles is, for all purposes, TA - the band's lineup has so far changed with every succeeding LP, and if there's another creative force present, I'm unaware of him or her).

That the band's ambitions bite more than they can chew creates some ironic tension: TA are proficient at basic, loudfastrules garage rock, yet they chomp at the bit at such restrictions - without, it being said, the instrumental capacity to achieve such sophisticated art rock ambitions. As such, the band stretch out their little indie garage tunes past the normal limits: they flip the punk aesthetic of in-n-out brevity on its head, with over half of these 9 songs hovering in the 5 to 7 minute range. The band's performances are just this side of stompingly energetic to get by, though on first listen the careening anarchic atmosphere sounds too scattershot - but eventually a hook to grab hold of pulls you aboard the freight train. Here, let me break down the album's flaws:

1) As I pointed out earlier, instrumentally the band are just semi-competent indie rockers, nothing special.

2) Strickles' voice is the most sonically identifiable deal-breaker: he screams hoarsely in a highly unpleasant manner that you either learn to tolerate or don't, and that I doubt anyone has grown to love.

3) The bargain-indie production muffles the vocals and performances to the point where most of the lyrics are barely comprehensible and the band sound at once tinny and densely cluttered. TA's poor arranging skills (at this stage in their development) may be equally at fault.

4) The default mode is "classic rock epic performed at punky speed" which makes the songs feel paradoxically long-winded and rushed (not to mention too all-sounds-the-samey). The drummer bashes away militaristically with no subtlety and the guitarists chime jangly with their arms in permanent strum: the band simply never lets up. And when they do, on the sole ballad, "No Future Part I", the album screeches to a grinding halt with the worst track. At this point, the hyper-caffeinated Strickles is utterly incapable of handling a slow one.

Those flaws are glaringly obvious, yet as is sometimes the case with young, fresh debuts by bands with potential greatness in them, Titus manage to overcome those defects with their youth and freshness. They play rock'n'roll with the enthusiasm of early 20somethings whose lives depend upon it, which is a rare enough commodity in these post-rock, neutered times. A little more seasoned expertise and sharpening up of their songwriting skills, and these kids could really have some potential.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Mott the Hoople - Wildlife

Wildlife (1971) **

Sneeringly dubbed "Mildlife" by the band themselves, Mott's third failed bid at basic competence consists mostly of stiffly performed, stalely written country-rockers (we'll get to the one notable exception at the end, don't worry). After the mindless, aimless, directionless downer Mad Shadows, the band overreacted wildly with a 180 change of direction - with equally disastrous results. And did I say country-rock? Actually, there are only two full-fledged rockers amongst these 9 tracks: the opener, "Whiskey Women," serves up lukewarm hard-rock riffage and groupie bashing lyrics to rock quite mildly. It's servicable but banally bog-ordinary early '70s rock, like a Bad Company side 2 deep track. It's sexist garbage and on most any other album wouldn't stand out in any memorable way, but in this context it does because it starts the album off on a deceptively energetic note. From that point on, we proceed to encounter a string of stone-faced, leaden ballads that are pleasant enough taken one by one, but in slowly torturous succession snooze me snuggily. The low point is either Ralphs' "Wrong Side of the River," a Neil Young ripoff that makes "Horse With No Name," sound like a boldly innovative stroke of inspiration; or the white hippie soul cover of Melanie's "Lay Down." The latter isn't as offbeat as it may seem - Mott were fond of covering contemporary hits live, from "American Pie," to CSNY's "Ohio," to Mountain - but this particular choice was completely inappropriate for the band's gritty hard rock talents and working class British attitude. The album is roughly split between Ralphs and Hunter sung tunes, and at this point, it's clear which one is the superior songwriter: all of Ralphs' songs more or less suck. Scratch that more or less - they suck emphatically with a capital E. Despite the band's genuine black country roots, they have as much genuine feel for American country music as Tom Jones. Hunter's tunes, on the other hand, ain't half bad. "The Original Mixed Kid," would've made a dandy contribution in a better context, and might be the best original composition here. "Waterlow," takes that honor, but it's problematic: it's a case of knowing the autobiographical circumstances (Hunter losing his wife and children due to divorce) giving the song that much more emotional heft. Taking that into consideration, his shaky singing and cracked voice add to the fragile tear-jerk power; on its own objective merits, however, the tune is a bit too wispy and the arrangement too murkily misty to hold together that memorably.

All that out of the way, we stumble upon the final track, and I do mean stumble - one can only guess at the shock of unprepared listeners in 1971 when the needle grooved onto #9. After an entire album of pleasantly bland soft country rock, appended as almost a bonus track is a 10-minute boogie medley of '50s rock'n'roll classics. It seems to have rudely barged its way in from another album, and in fact did - given that Mott were routinely selling out shows in Britain due to their intense live performances, it was proposed that a live album be their next release. If only - it would've made a smashing idea, but sadly only this 10 minute remnant survived to be tacked on to Mott's mellowest album. Whatever - it demonstrates that Mott were indeed one of the hottest live acts of their era. It's not enough to make up for the soporific offerings of the preceding half hour, though.

Trivia note: Hunter incorrectly credits Ray Charles' "What'd I Say," to Jerry Lee Lewis. Not that it matters - Hunter's enthusiasm is clear. Not like Frank Sinatra introducing "Something," as by Lennon/McCartney.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

H

H